When 16-year-old James Griffin was a high school student in rural Ohio, he bravely lived his life as an openly gay and free-spirited young teenager. He wore flamboyant clothes and polished his fingernails. He dyed his hair from week to week and wore it in various fashions. He was active in the his high school’s drama club and he was the captain of his school’s cheerleading squad. He was very popular with the girls in school but some of the boys steered clear of him during classes for fear that they too would fall victim to the bullies in school, many of whom taunted and beat up on James Griffin.

When 16-year-old James Griffin was a high school student in rural Ohio, he bravely lived his life as an openly gay and free-spirited young teenager. He wore flamboyant clothes and polished his fingernails. He dyed his hair from week to week and wore it in various fashions. He was active in the his high school’s drama club and he was the captain of his school’s cheerleading squad. He was very popular with the girls in school but some of the boys steered clear of him during classes for fear that they too would fall victim to the bullies in school, many of whom taunted and beat up on James Griffin.

In the fall of his sophomore year James received the school’s Drama Club award. When he went up on the auditorium stage to accept the award, he said that he was proud “as a gay student” to accept the award. Before James could get to the next sentence of his speech he was hit squarely in the eye with an egg thrown by the varsity baseball team’s ace pitcher Gregory Hill. James was knocked unconscious and spent nearly three weeks in a hospital where doctors feared that he might lose the vision in his eye because the force of the egg hitting his eye at such high speed had compressed his optic nerve.

Gregory Hill, who was at that time a senior, was arrested and charged as a juvenile with atrocious assault and intent to do bodily harm. He was sentenced to two years in the adolescent corrections unit and was expelled from the high school. Meanwhile, James Griffin recovered from his injury with only a 20% loss of vision in his eye. Doctors were originally optimistic that his vision would gradually get better but by the time senior year rolled around, it was determined that the affected eye would not improve. James didn’t complain and told friend he “could live with it.”

In the spring of junior year, one of James’ classmates was diagnosed with leukemia and was in desperate need of a bone marrow transplant. Many of the students — James included — went to be tested to see if they had the genetic matching so that they could possibly donate the bone marrow. James’ genetic markers did not match but a week after the tests, James’ family was contacted by a local hospital who told him that James was a perfect genetic match for a young man in a Cleveland hospital who desperately needed a kidney transplant after having destroyed his own kidneys by drinking dry cleaning fluid in an attempt to commit suicide.

“My wife and I really had to think about this,” said James’ stepfather Earle Codey. “We only knew an anonymous young man one hundred miles away was dying we knew that our son’s kidney was the only hope the kid had, but we didn’t want to risk the health and safety of our boy. I’m not James’ biological father but I have been married to his mom since James was a toddler. I consider him to be my own son.”

When James got news of what was going on, he immediately said that he wanted to donate his kidney to the dying boy – a 19-year-old kid who was living in a group home in Cleveland,

“We resisted at first,” said Codey, “but James insisted that we at least go and visit the boy so that maybe a connection could be established. The boy had been denied 12 donated kidneys because of his unusual blood type and he was slowly dying. Even with dialysis, his entire body was weakening day by day.

“We let it run through our minds for days and days until finally we got a phone call from a genetic counselor at the hospital. She told us that not only was James a perfect genetic match for the young man who needed the kidney, but that genetic testing showed that the James and the boy had to be biological full brothers. Those words fell on me like a ton of bricks and I asked if there was a possibility that this was just a coincidence, but the counselor said the odds of that were a billion to one.

“Finally my wife started crying and admitted that she had had a baby boy almost two years before she met me and that she’d given the baby up for adoption. I held my wife tight in my arms and I knew we had to make a decision then and there.”

The Codey’s took James to the University Hospital in Cleveland to meet the sick young man, but it was James’ mother, Bernice Codey, who was the first allowed inside the room so as to re-introduced her to the son she had given up for adoption 19 years earlier. The two had an hour of privacy together and then when James came in he was shocked to find that not only was the boy his brother, it was Gregory Hill — the boy who had mercilessly bullied James in high school and had thrown the egg that had permanently damaged his right eye.

Bernice Codey did not recognize the boy as her son’s attacker because she’d only seen photos of him in a small local newspaper at the time of the attack and had only seen him in passing during one court proceeding. Obvioulsy Greg had changed a great deal since then. His large athletic frame had withered down to nothing but James and Greg recognized each other instantly.

“I talked to Greg for hours and hours,” said James. “He was actually a nice guy…but not just because he wanted my kidney. He said he was just happy to find out that he had a family. He said that he grew up in a foster home until he was seven and that he got to be really good at pitching baseballs because he had no family and he would spend hours throwing baseballs at bales of straw on a farm where a foster family made him work 10 hours each day.

“He told me he was sorry that he hurt my eye and sorry that he always picked on me. He told me that he did not want my kidney and he didn’t deserve it. He just wanted to me to sit and talk with him until he went into a coma or died. He said he just wanted to be with his brother. He said that he was a loser and his lfe meant nothing. He said he had the talent to throw a hard fastball but he wasted it hurting another kid just to try to act tough.”

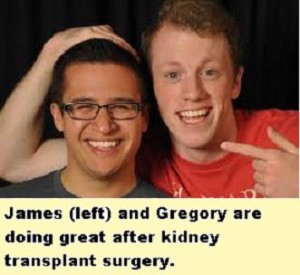

Two days after this meeting, James convinced Greg that life was great and that with a new kidney he would be fine. Finally after a week of psyhological counseling, Greg agreed to take James’ kidney and the operation was a great success. It was actually more dangerous for James than it was for Greg. James was in the ICU for three days whereas Greg was up and about the next day.

Four years have passed since the day of the transpant. James has married his longtime boyfriend Kyle Marx in New York in April of 2013, and Gregory, the bully who used to beat him up and nearly cost him his vision, was standing there as both Best Man and as a loving brother.

“The odds of something like this happening are a trillion to one,” said a physician who worked on the transplant team.

“It’s easy to see how the boys never put two and two together. They did not look alike and their personalities were very different, but county records and genetic testing proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that they are full brothers. You couldn’t get a better match for a kidney donor — even with full brothers this is a rare match. Greg has a long life ahead of him.”

Today James lives with his husband Kyle in New York City where both attend university classes and plan on opening a photography studio. Greg lives at home with the Codey’s who he proudly calls “his parents.” He’s had some ups and downs with his overall health with stomach troubles that were originally caused by his suicide attempt and subsequent kidney failure, but things are great now and his kidney is working fine without a hint of any rejection. This summer he started working full time in Earle Codey’s construction business, and in September Greg will start classes at Ohio State Univeristy where he plans to major in child psychology.

NOTE: Although the names of the parties involved have been altered, some sick readers have gone through the trouble to locate the real family and some of you sickos have said some unkind things. This story is here to inspire love — not hatred. Kindly do not bother either of these two young men or their families.

Editor’s note: John Griffin, the biological father of both boys was a man with whom Bernice Codey lived for five years. He died from complications of pulmonary hypertension when Bernice was pregnant with James.

NOTE: Commenting here on The Damien Zone is very easy. We do not cross check emails very often and the only drawback is that you have to wait a bit for your comment to post. The Damien Zone does not censor comments — unless it’s somthing outrageous. Be patient — your comment will appear. Keep checking back. If your comment annoys or impresses the editor, he will personally address it.